Move fast and break things? Or slow and steady wins the race?

While researching a topic at work, I was referring to several conference talks as well as blog posts on how to evolve architecture of systems in a practical manner taking in to account the human element. In between getting my self bored and going “aha!”, very loudly to the utter annoyance of my kids, I managed to gather some good insights. But the breakthrough came when a colleague mentioned the fact that product as a discipline always seem to have urgency in mind. Everything needed to be done now or even better still, yesterday. So what drives them? Are they truly evil? Out to foil the genuine do-goodder attempts of development and architecture teams? Or are they simply misunderstood most of the time?

Understanding the product drive to get things done

For this, it is essential that you develop empathetic views of the various disciplines involved in the process. The whole point of the product development as a discipline is to map out a roadmap for the product that the users of the system will find useful and will be willing to pay for. For them, the clients are the users of the system. And I am using the word ‘client’ here to mean the immediate group of people that the particular discipline’s work OKRs are impacted by. For product, this group of people is the immediate users of the product. And the most universally effective way of keeping them happy and hitting the related OKRs is to deliver what they want, before they want it.

Now there does exist the odd bad product team, but disregarding the concept of cartoonish evil product teams, mostly they want to be able to deliver features to their users. They do understand that the delivery of features does not happen in a vacuum, that it happens within the context of the platform. They do understand that features should not increase the overall complexity of the platform as much as possible and make the development of features in the future as easy as possible. If they do not understand this, the team leads, tech leads, and the engineering managers should get better at communicating this aspect. I understand this sounds glib, but it is true - there is no solution for insufficiently good communication. And how to communicate effectively is several full books essentially. So that will have to wait!

Handling the quick wins

So it is a fact of life that product will keep on asking for quick wins but what can we do about it? Two courses of action and one question - How costly is it to reverse your decision? Your course of action will depend on this one question and you should know the answer quite confidently. Can you reverse your decision given the architectural changes this decision will entail with a reasonable cost? If the answer is yes - do the change, if the answer is no - do not do the change.

Do the required feature as a quick win

Do play along and find a way to deliver the same effect as they are asking for. Assuming that the feature does not adversely affect the architecture of the platform no matter the implementation, great no issues then. But assuming as almost always there are several different ways to get the same thing done and the quickest is the dirtiest, how do you deliver the work? You compromise and say we will get you the feature in this manner and it will take 2 weeks instead of 6 but it is going to be hacky and we will need to take another 4 weeks to refactor so this feature does not impede us in the future. Weather you use branch by abstraction, feature flags or a combination, the concept remains the same - the audience gets the feature quickly and product are happy. Engineering gets to tidy up the implementation and they are happy. As a bonus point, often there will be some feedback from the client in the middle of your refactor which you can just incorporate into your code and make the implementation better. But remember this all depends on you being able to change the initial quick hack you deliver to a proper sustainable architecture afterward.

Don’t do the required feature as a quick win

If the required feature cannot be delivered as a quick win and requires long term platform building work to be done first, do not give in and do it as a quick hack. It may be tempting given that it will make the product team happy and will definitely make your life easy. But understand that you will be paying for this decision later on when it breaks your team’s agility. The most important thing though is not the “No, we cannot” but “This is how we can do it”. A can-do attitude is worth its weight in gold in software architecture/development lead land because so many of us will stop after the initial no. Plot a course for the product and communicate what needs to happen in order for you to build this feature. Break it down into the smallest parts possible and explain each one. The changes are these steps can be reused for some other purpose and if the product can align their feature roadmap along those lines, most of the time you will get the go-ahead to implement the long term architectural plan.

Cathedral building - one brick at a time

To expand on the second answer above, because the first answer is quite simple and requires no elaboration, let us consider a simple media streaming solution. Your product managers ask you to implement a feature that allows your curation team to put together a Christmas playlist for the app. Now say you do not have a good way of putting custom styling on this play list to match Christmas theme right now. How can you achieve this? One way would be to refuse to do custom styling because this is a one-off thing that won’t last beyond Christmas and you don’t want to do a quick hack on the client side because this information should be propagated through the backend to be a proper sustainable, uniform implementation in the long run.

But going beyond that, you can suggest an approach like this.

- Implement the styling as a quick hack but make sure to get the styling data from an opaque interface ( let’s be original and call it StyleProvider )

- Get this in front of internal testers, accessibility teams, and beta testers to get feedback

- Meantime let backend team do a quick implementation where they put the styling info in an app config and directly serve it as an API

- Connect frontend to this API and use that to create the proper styling

- Create a proper styling authoring tool that writes to the config that the curation teams can use

Now this may sound very much like a cathedral-building exercise but understand that we had already shipped things to clients at #1 and we have a sustainable architecture at #4. You may be surprised at how many product teams you can convince to go with this approach.

How to approach compromises

I do kind of make it sound too easy in the above example as you can see. In the real world, it is rarely that straightforward and you have to take in different actors in the system and how they interact. But the gist of the approach remains the same. Make sure that your product team understands that you are

- Doing them a favor by prioritizing feature delivery against creating technical debt in the short term

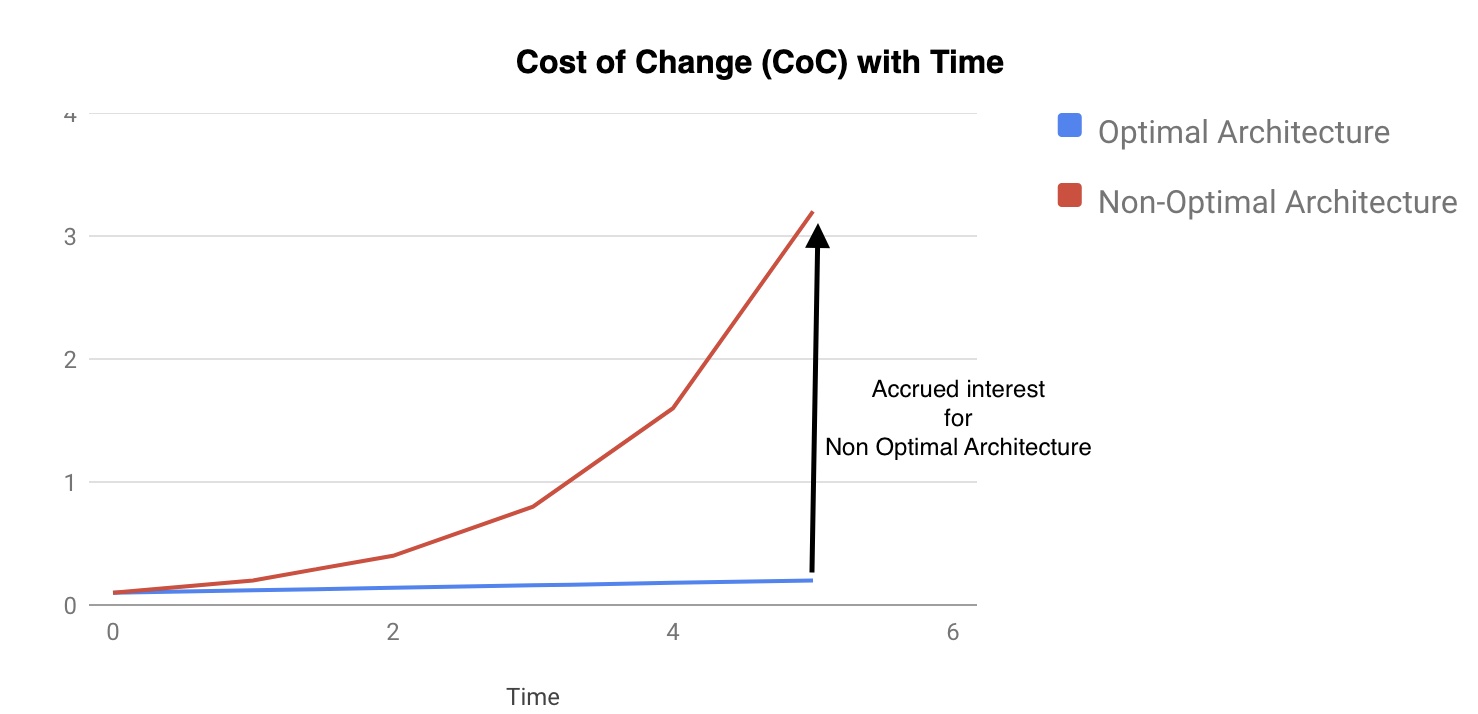

- That this technical debt must be paid off before interest accrues in the long term

Remember, debt is good if the use that you put that debt to is good. Mortgages allow you to live in a house now and pay later. But they are not good if you neglect the debt, do not service it and have no regard for the resulting architecture. You should always plan for and execute a refactoring strategy so you are not penalized in the long term for this technical debt. Remember - technical debt has an interest that you need to pay!

Technical Debt and the Interest Accrued

Make sure that this compromise is front and center in all discussions. It should be the basis of all discussions. Once you have done something similar, you would have built up some trust and comfort for this approach which you can reuse going forward. Once the team and stakeholders are comfortable with this approach, it becomes much easier to get people’s buy-in by pointing to previous examples of good execution of this idea.

Coming back for the refactor

Now, you will be tempted to call the follow on work from the initial implementation as “Clean Up Work”. I think this will be a mistake - impressions matter and this is the wrong impression to make. Refactoring will be a more suitable and a neutral term that communicates the fact we are not making any changes to the observable behavior of the implementation but just making sure the work is arranged in such a manner as to increase comprehension for engineers and to make it easy to build on top of. There are a few ways in which you can do this.

If like most organizations in this time you are using some sort of a agile project tracker, you can create two projects or epics for each phase of the project. First phase will last from initial ideation through to delivery of the quick win. The second phase will start from just before or after that to when refactoring is completed and delivered to production with all the client feedback. Another way might be to treat this as a single epic but create all stories beforehand. Now if you use a concept like branch by abstraction you can even have two teams working on two phases at the same time.

You can also make use of other tooling such as feature flags for de-risking the actual production deployment. The key thing is to remember that whatever tools or techniques that you end up using, they should be used with a good process in place. What I mean by that is there should be a well known process, preferably documented and accessible easily that describes how all these tools are used in shipping features quickly. Then there can be no confusion regarding architecture and how it is made sustainable. Otherwise you will be doing that communication work every time this kind of compromise happens. Do the work for documenting these processes beforehand and save yourselves a whole bunch of time.

Follow-ups, Demonstrations, and Retros

It is probably a good idea to demonstrate these actions in a retrospective about the project. If this is not standard practice, schedule a one off meeting and show it to all the stakeholders. Demonstrate the narrative of Engineering delivering something in short term by compromising ideal architecture, and recovering and perfecting the result with feedback and getting back to idea architecture. It is probably a good idea to keep a list of these occasions and their details. You would likely want to refer to this for further details, weather it is to come up with a future estimate, to recount a good year or for new team members, stakeholders or leadership to get familiarized with how compromise works in your team. It will help bring them in line with the rest of the team.

Banner Photo by Desola Lanre-Ologun on Unsplash